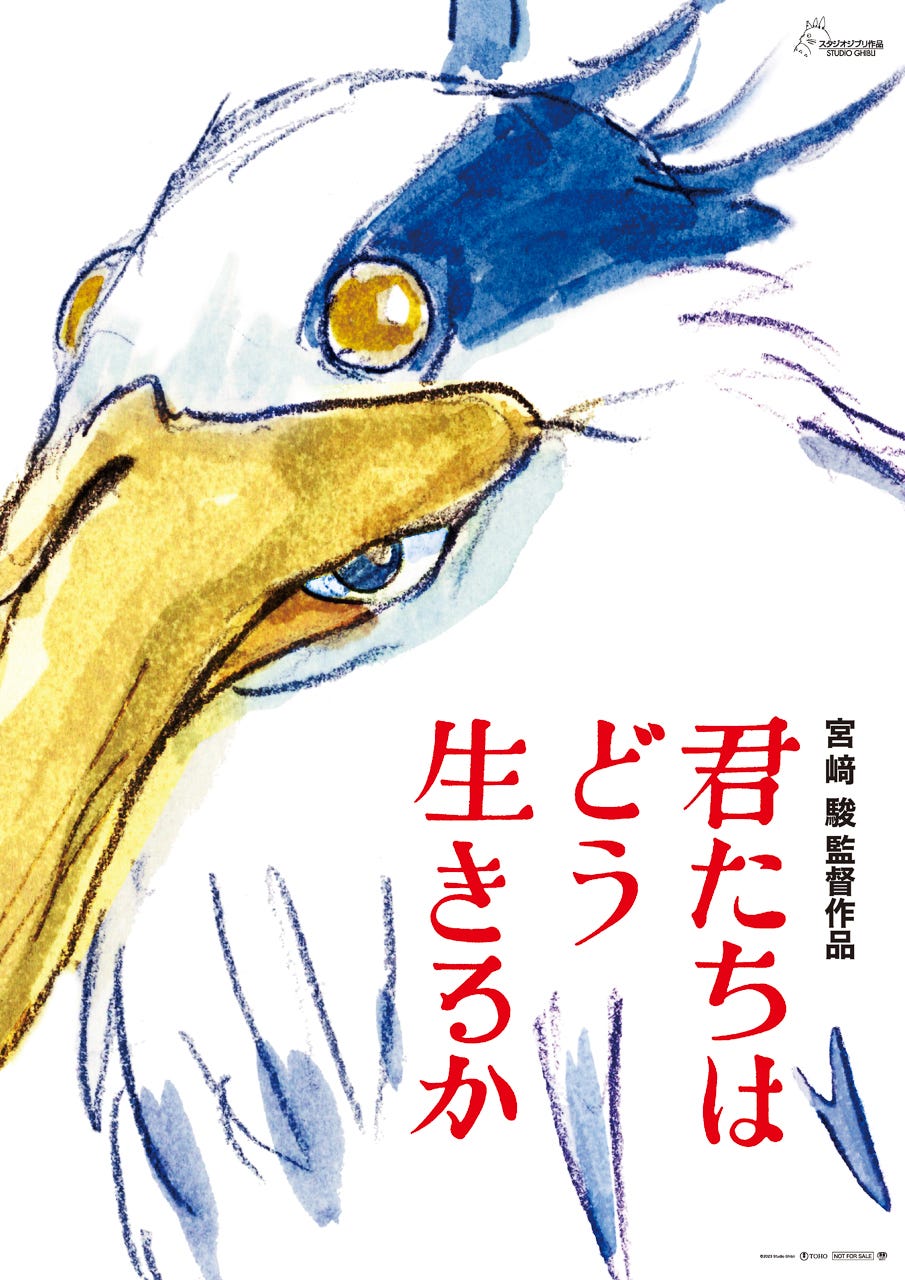

The Boy and the Heron Review (Or, How Do You Live)

Full spoilers of Miyazaki and Ghibli's latest film, 君たちはどう生きるか

Today I got to watch “The Boy and The Heron” (Although the title "How Do You Live" is a lot better), Ghibli (and Hayao Miyazaki's) latest (and potentially last - at least for Miyazaki) film.

The first thing is that if you want to watch the movie at any point I recommend you stop reading here and come back to it after watching it. I recognize that it’s slightly in bad taste to be posting a full spoiler review so early, but I really needed to get my thoughts in order…

...

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The Short Review

I think I will remember this movie for a long time and it has given me a tiny existential crisis

...

..

.

.

.

Are you sure you want to read the review? Last chance to turn back…

…

..

.

.

Okay then!

Plot

Okay, now then... Unfortunately I can't guarantee the details are 100% right, mainly because my Japanese listening isn't perfect, I don't have other writing to compare this against, and it's a bit of an obtuse story in the sense it doesn't spell everything out for the viewer. So read this knowing that it’s maybe 80%-90% ‘right’ with the plot details.

The movie starts during a firebombing of Tokyo in WW2. The protagonist, Mahito, a boy of around middle-school age, loses his mother, I think to fire. This is an extremely intense scene, I can't really describe it but the animation is frightening and visceral in a way with how Mahito runs through the streets.

Almost immediately after the bombing, Mahito and his father have moved to the countryside where his father has a factory, manufacturing what appear to be cockpit windows for planes (they are very elliptical and rounded). The father has remarried to his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko, who is pregnant. Natsuko is (Of note here is that Miyazaki himself was well-off growing up, his dad working in manufacturing for the army)

Natsuko's family estate is very Japanese-style, but there is a single Western-style home there where the family of 3 live. They are a rich family: the estate has many servants. Mahito isn't pleased to be living here, he's bullied at school, probably from being rich, and after the first day he strikes himself in the temple with a rock, wounding himself deeply. This scene is fairly graphic by Ghibli standards, he bleeds out a lot, it left me thinking about instances of visceral violence in other Japanese postwar fiction like Kenzaburo Oe’s The Silent Cry .

There's a strange, ruined, library-esque castle near the estate, built/owned by a man who read a lot of books and vanished one day. I didn't fully catch the details, but this man appears later.

The movie takes on a sort of surreal mysterious / very-light-horror tone, until Mahito enters the 'otherworld' in search of Natsuko. He meets and travels with various characters, one at a time - the humanoid version of the Heron, Kiriko, a fisherwoman (with the same scar as Mahito), and Himi, a girl with fire magic.

There's a lot of world-building in the rest of the movie that isn't gone over in high amounts of detail, but is interesting. I'll leave this out for now though.

Eventually we learn about the herons and bird-people living in this otherworld. It's implied their kingdom is cursed or falling into ruin or something, and their leader tries to bargain with "God" (the old man who lived in the castle near the estate - actually Natsuko's great uncle) to save their kingdom or something (I might not be getting the details right here). "God" (not the official name) seems to be having trouble building worlds, and the movie ends with this otherworld essentially crumbling/vanishing.

God was asking Mahito if he wanted to take over, or something, but Mahito just wants to leave and doesn't see himself as fit.

All the main characters escape the otherworld safely through this 'hall of doors,' which leads back to separate 'human worlds,' I think - not sure. Either way, Mahito and Himi go their separate ways at the end (Himi is revealed to be a past version of his mom from another world.)

Mahito does manage to escape with a small, white building block - which God would use to 'build worlds' (I think.)

Cut to a few years later. Natsuko has delivered her child and Mahito and his family are going to move back to Tokyo.

REVIEW

The Air Raid Scene

The movie starts *with air raid sirens,* before Tokyo is firebombed by Americans, and Mahito's mother eventually is implied to die. It's a terrifying scene, I think played out without any or much music - just the protagonist getting ready and running out into the streets. The animation here is really worth noting - as Mahito runs through the streets, there's this sort of smear/melting effect on all the people he runs by. It's almost a little disturbing? I really want to see it again, haha. There was something very powerful about it, especially where I was watching it - in downtown Ikebukuro in Tokyo where there *were* firebombings during WW2. I wonder what Japanese viewers thought of this decision, it certainly felt like a surprise for me. It was interesting, maybe fitting, to watch it at Grand Cinema Sunshine, related to Sunshine City*, a nearby mall built on the former site of a prison for pre-war political prisoners and post-war war criminals.

The bombings aren't really referenced in the rest of the movie, except for some symbolism and flashbacks of Mahito.

It's such a good decision - for one, it clearly grounds the movie in a particular moment and reality. I really feel blown away by this opening scene, it’s such a genius move to put that right at the start…

I think it plays with expectations in a good way: the first 40 minutes of the movie are in 'reality,' and we're *constantly* wondering when the advertised fantasy is going to appear. And it does appear, slowly, in bits and pieces.

Slow Reality

I was surprised by how slow the initial 1/3 of the film is. There's so many shots that just linger on the space of the estate, or Mahito's emotions. Mahito falls in and out of sleep, strange things happen that other characters deny, there's an overwhelming sense of being trapped in this expensive estate, every whim catered to, with Mahito only nagged by the heron who constantly tries to get him to enter the fantasy world.

The slow pacing gave ample time to think about Mahito's situation in a way I’m only used to seeing in more arthouse films or stuff like Taiwanese New Wave films. Here's a kid, socially isolated, forced to live with a stepmom and servants, torn away from his home in Tokyo in a time before instant communication. The film spends all this time establishing an 'anchor' for us in historical reality, I think, so that the looser fantasy sequence is a little less disorienting.

Lastly, there's a subtle horror to the way in which Mahito is expected to stay in his bed, with Natsuko trying to keep him away from the strange building near the estate, servants mentioning how much Natsuko looks like Mahito's mom, and his dad trying to constantly find out who 'hurt Mahito' (Mahito lies about his self-inflicted wound, saying he fell.)

It's worth mentioning that Mahito feels very formal and emotionally closed off for a boy, even aggressive.

Fantasy

So the last 80 minutes or so of the movie are in the "otherworld" - this kind of fantasy 'underworld' of sorts (I say underworld because Mahito falls into this world by falling through a floor.) It looks like a combination of various elements from many of Miyazaki's past works. There's bug-filled jungles, open grassy plains, wide-open seas, overgrown ships, eurofantasy-esque towns, cottages. There's spiritual systems of life and death shown but not fully explained - empty silhouettes of people rowing across the ocean, little bubbly spirits who are supposed to go to the 'world above' to be born into humans.

What's most notable to me is the way in which so much of the world goes unexplained. I really like this effect, even if it's a bit disorienting. We never really get a sense of what the geography of the otherworld is, instead the movie jumps between various landmarks, sometimes to a disorienting degree. We see these aspects of world building, these narrative settings that feel like they could carry their whole entire plots themselves, but ultimately the feeling it conveys is that the otherworld in HDYL is a place in its last days. It feels a bit like... seeing the various stations in Kenji Miyazawa's Night on the Galactic Railroad, or maybe the absurd stops in Abe Kobo's Kangaroo Notebook. It’s a narrative effect I like: withholding the continuity of space in exchange for a world that feels very deep.

Mahito is only here for a rescue mission, he's not here to save the world or anything. A dying talking heron says the otherworld is cursed, and the herons and birdpeople living in the otherworld seem desperate and hungry for anything (especially humans.)

Most disturbingly is the level of apocalypse here - it's I think only subtly rendered, but the entire otherworld crumbles at the end of the story. Mahito constantly comes close to death, barely making it back to his home world.

So what *was* the otherworld? I'm not exactly sure. It's possible the film explained it or left the clues but I got the sense it was up to interpretation, to an extent. Like if it was an afterlife then what's the implication of it crumbling away? Why was the heron saying stuff about Mahito's biological mom at the start of the film? Why was there a myth amongst servants about something falling from the sky? Anyways.

There's an old man, I guess, "God," who I think is maintaining or building the otherworld. He sits in a grassy field, with a gigantic, ridged and floating black stone near him. He doesn't seem too stressed about the fact his ability to build/maintain worlds isn't going too well. At one point I think he offers Mahito the option to try building worlds, but Mahito refuses, preferring to return to his home world. When Mahito DOES manage to return, he leaves with a small white block in his pocket - similar to the ones God was using to build worlds.

The movie doesn't explain what this block does (I think,) but to me it feels like.. trying to convey that Mahito has some choice in the matter of how he builds his world. Maybe not on the level or scale of a God, but there's so many problems in the real world, even right at Mahito's doorstep, with his father's factory, etc. To me the God character felt like that overstudious person, endlessly trying to find the right argument or knowledge that will settle every debate and matter once and for all. And of course, that can't really work... every human has to accept the scope of their life at some point, unless their ambitious grow destructive.

How Do You Live

So what purpose does the whole fantasy section serve? Well, notably, right before that section begins, Mahito finds a book his mom has signed or dedicated for him - and it's How Do You Live? - presumably by Genzaburo Yoshino (although I couldn't catch the author's name). It’s a novel about a teenage boy whose father died, and his correspondence with his uncle (who gives him socialist moral lessons.)

Mahito reads it and I believe is emotionally moved. Shortly after he decides to go into the forest to look for his stepmom, starting the fantasy sequence. Was he motivated by the book? Or something else?

Like much of the movie, that's left up in the air. It's refreshing to see this in an animated movie, as it's actually one of things I really love about movies and novels, or stories in general - giving a viewer enough to work with, but leaving stuff up to interpretation, without resorting to overly-obfuscating techniques like extremely complicated lore. While those things are certainly fun, I generally find them to be less memorable/moving in the long run, as they shift too much focus onto the act of interpreting rather than thinking about the story content itself.

HDYL feels very *visual* to me in this way. I don't mean *visual* in the sense of fancy punching animations or fighting scenes, but I mean that HDYL really feels like it leans into animation and film *as a medium,* rather than being something that merely adds art to a written plot. Like our real world, like a photograph, or any given movie on anyone’s iPhone, the visuals contain an unknowable depth. I always like my media to not explain everything, to be a little confusing. I think it can knock things loose in us better that way.

Maybe I'm being too generous, though... I think this will be divisive amongst viewers!

But I overall found it kind of beautiful how we don't get the whole picture of HDYL's fantasy world. We only see it in its last moments, a fleeting glimpse, told through the eyes of Mahito who is barely scraping by.

Miyazaki

It's impossible to watch this without thinking about Miyazaki's mortality and repeat 'retirements.' I can't imagine making an animated film is easy in your 70s and 80s. What do you choose to say at that point? What do you do with your influence? What HDYL conveys is something without many easy answers... it gives us the main bits - the postwar reality, this crumbling fantasy worlds - but then also gives the space to think through things on our own. Maybe it could have used a bit more, but I really think as a work of animation it’s just interesting to think about and have in mind.

Miyazaki has always been a weird figure for me. For one, I'm not a huge fan of all of his work - I don't *dislike* his work, but I definitely have my favorites (Totoro!). But there's something to his cynicism that resonates with me and also gives me pause whenever I'm ranting about this or that with the games industry. Miyazaki has, I think, legitimate grievances with the Anime industry. What's one of the most interesting mediums to me, instead, seems to be mostly wasted on the the Light Novel to Manga to Anime to Merch pipeline, which only financially rewards a chosen few, overworks many, and leaves non-fans groaning at the sight of another anime-themed coffee can or vending machine.

It leaves little wiggle room for artistic experimentation or exploration, mainly choosing to give mostly-safe stories with always-marketable and merch-able characters with idealized body shapes and faces. It's unfortunate that animation is as costly and difficult as it is, as it leads to fewer voices able to work in a longform format.

There are similar problems in games, of course. This isn't the place to rant about it, but it's definitely exhausting being a games creator for over ten years, and there are many moments of it feeling defeating... While my work gets recognition and appreciation, at the same time I'm always recognizing that it's not *changing* the overall landscape, no matter how many complicated themes we layer or structural twists we put together. But it’s important to recognize, or maybe merely self-affirm, that I should be here to do nothing less than express my love of games.

Looking at Miyazaki's cynicism of his own industry (at least in the few media clips we see of him) reminds me that I shouldn't fixate on that feeling of self-defeat. It's an easy emotion to wallow in, but I think it's emotional energy pointlessly spent. Of course no one person can change something like the anime or the games industry. There's a place for anger but it should always be a springboard to something else, not a swamp.

And I think it’s worth considering that maybe HDYL is Miyazaki getting over that cynicism?

Overall, how I read HDYL is:

Maybe, like Mahito, we can just take a little, small piece of the world, act on it in your own way, and see what kind of ripples spread out...

5/5

* Being at Grand Cinema Sunshine feels personally relevant as well as Sunshine City was the direct historical and visual inspiration for one of the levels in one of my games, Sephonie

I'll put some corrections in this thread: first, they move to the country estate right after the bombing, he hasn't had time to process his mother's death.

For a complete overview and full spoilers this video was a really great summary and matches with my remembering. https://youtu.be/CyAqwpH5aNM