The more you study videogames, the more you realize their origin can’t simply be pinpointed to some MIT nerds making Spacewar! in the ‘60s. Their origins lay in 1800s visual entertainment (see this Huhtamo piece), humanity’s desire for play and roleplay, written media, and more.

In Eric Hayot’s article, Video Games & The Novel, he says we should view games as related to how interaction has been utilized in other narrative mediums. These include theatre, or spoken poetry, where “the line between story-world and audience [becomes blurry]”. Imagine someone reads a poem, out loud, and it’s about heartbreak. A line resonates with us: we make a personal interpretation. Whether it be related to heartbreak or something else, we’ve interacted with the poem.

Often, the writing I do for games tends to be scattered throughout the game - you could call it miscellany. This includes lines spoken by NPCs here or there (in Anodyne), descriptions of areas or items (in Angeline Era), the inner thoughts of creatures (in Sephonie), or the meta-ramblings of postgame content in Anodyne 2 or Even the Ocean. I’ve found that this style of writing feels distinct from something like writing a longer, dialogue-focused cutscene, whose traditions can be located more within movies or novels.

Today I’d like to think a bit about some other mediums of text or visuals which feel relevant to the decisions I make when writing miscellany.

Theatre

Perhaps the more obvious one. Why? The playwright writes a line, but, it will be interpreted differently based on the director, the actor, their moods on the night of the performance, etc. On top of that, the way we watch plays is somewhat like a game. Each audience member has a different viewing angle of the stage, free to shift their gaze around the theatre. When multiple things are happening on stage, this gives multiple choices to focus on.

Check out 1:03 in this preview of a Takarazuka play I saw last week. In case the video is taken down in the future, the video shows two protagonists, one having a conversation with a side character, and the other sitting off on his own.

The feeling of viewing this is different from focusing on the extras in a movie. With theatre happening right in front of us, our attention is split between different actors or objects, like everyday life when our attention might be split between an important train announcement, picking a soda from the vending machine, or answering a text. The combination of variables in what an audience member gets out of a script’s line reminds me of the variables in a game’s line of miscellany. A player might skim over some text because something else is more important. Maybe something in their real life is weighing down on them. Maybe they miss the text or come to it at a way later point in the game than intended.

When I think of miscellany, I think of the potential for misinterpretation. In some ways this is miscellany’s power — it opens up the player’s imagination. And it’s this potential for misinterpretation that’s a valuable reference point when considering other mediums containing text, like theatre, or less conventional ones like conversations or folktales.

Conversations

When we try to say something to a friend, we may feel unsatisfied with our explanation, or, filter and adjust what we say. Eventually we settle on some way of communicating, and let the friend respond.

The friend will go on to process what we said in their own way, and, the conversation carries on. If we were to recount the same idea to another friend, it will almost always come out differently. But, we are okay with this blurriness between the idea in our head, and how it comes out when spoken. And, we are okay with the idea that each part of a conversation can be viewed as a little puzzle piece that our friend will use to color their perception of ourselves.

Conversation often includes rumor, even when talking about ourselves. Couldn’t saying that “Yeah I feel okay” be a way of moving the conversation forward, without being true to our emotional state? Put another way, how we view and navigate the world is ultimately based on the synthesis of rumor-like tales, anecdotes, fragments and pieces of people and events. We place faith in this steering ourselves to good decisions.

In the way that a single thing (perhaps a spicy anecdote or rumor) we hear in a conversation can spark our imagination, the same applies to writing miscellany. Take an example of this simple area description from my upcoming-bumpslash-epic-wishlist-on-steam-today-Angeline Era for a cave level, which you might miss. But if you read it, it offers a little bit of context to the strange monsters and challenges within.

The Spider Fae dream of home: the Otherworld.

And so they dance in their sleep, fruitlessly yearning for visions so vivid..

“Dance in their sleep,” “visions,” “the Otherworld…” potential for misinterpretation is everywhere. The implications and imagery behind these terms are ultimately up to a player, as well as if they’ve encountered similar terms throughout the game. And to be sure, we do try to use the terms in other text throughout the game, so as to allow for some level of coherent interpretation.

By using these descriptions as a springboard, they help a player form a fuzzy notion in their mind that circles around the idea that “this is a game world in which Fae have desires, and in which the Fae are living away from home.” The point is imply, or even argue for, a richness in Angeline Era’s world that we couldn’t convey otherwise.

Folktales (Legends of Tono)

A collection of folktales may clue us to another culture, but they rarely tell a conventionally coherent narrative, instead giving us a fantastical fragment of another place and time, whose fact or fiction is hard to untangle.

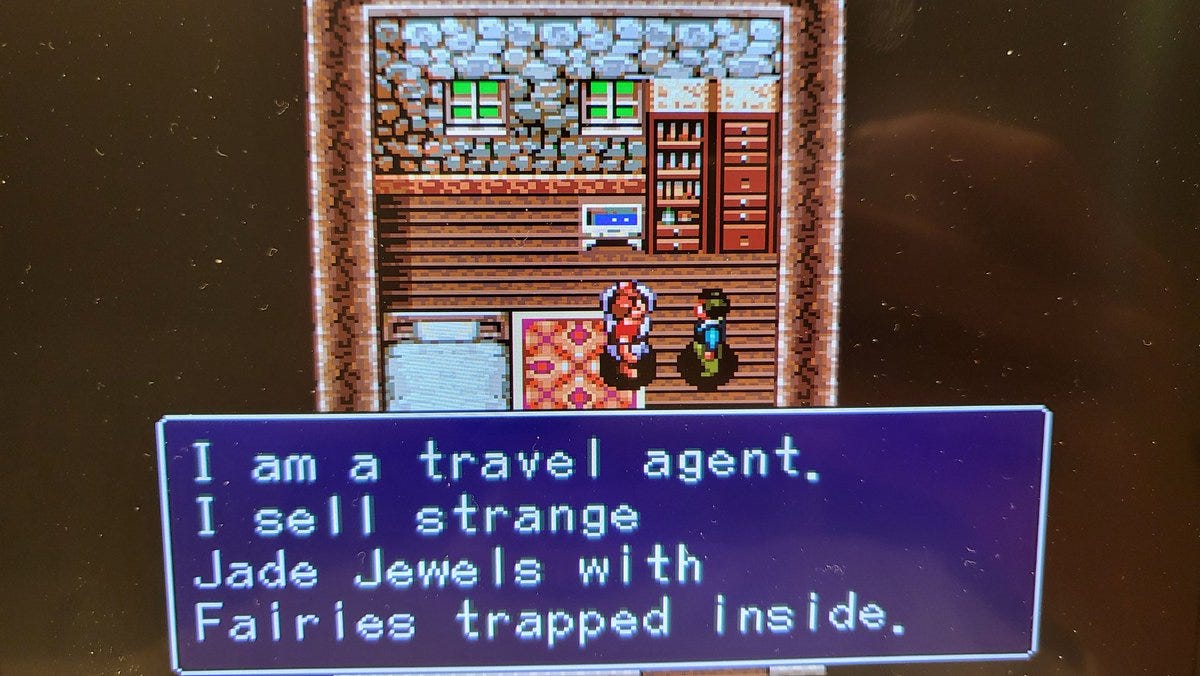

There’s a lot to how folktales function that are similar to the games’ miscellany. Some miscellany instructs you about specific qualities of the game world: A strange village, a group of creatures, a rumor. Some are one-off jokes, like looking in an NPC’s drawers. They each tell a tiny piece of the game world, but in a slightly uncontrolled way. Just how much are we to imagine, say, from a one-off line of a character standing in a lake?

Take the Legends of Tono, a collection of folktales recounted by Kizen Sasaki, then edited by Yanagita Kunio. They offer up fragments of Japan’s Tono area to try and piece together. Here’s one of the stories:

An old man named Yanosuke Kikuchi led packhorses on the trail when he was young. He was a good flute player and would play during the night while leading the horses. One slightly cloudy moonlit night, when he was going with a group of friends over Sakaigi-toge (boundary-tree pass) on the way to the seashore, he took out his flute and played just as they were passing above a place called Oyachi. Oyachi is in a deep valley thick with white birch trees. Below it there is a swamp with reeds growing. Just when he played the flute, someone at the bottom of the valley cried out in a loud voice, "Hey, you're good!" It is said that everyone in the group turned pale and ran off. — The Legends of Tono (100th anniversary edition), page 16

When I hear “Hey, you’re good!” I immediately think of some kind of gag in a game where you can play instruments. You take out your ocarina (or whatever), flub a few notes in a grove where you think no one’s standing, and then, a random text box: “Hey, you’re good!” Are they kidding or serious? Is this a joke or an actual character? The room for interpretation is wide, and it parallels how we choose to react to pleasant or unpleasant experiences in real life, too. (Was someone having a bad day, or a bad person? And so on.)

Most of the Legends of Tono is like this - very short tales with little context, painting a small slice of whatever culture Kizen Sasaki came from, occasionally giving some insight into beliefs or daily life of that culture, but with an additional layer of uncertainty introduced from Yanagita’s editing.

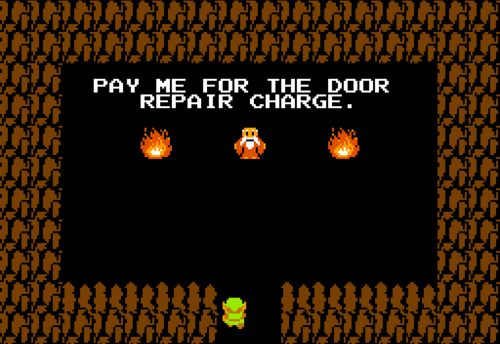

I’m struck by how much it makes me think of talking to all the characters in an RPG town: there’s talk of important people (Yanosuke Kikuchi), details about the culture (flute playing to lead horses), the local region (Sakaigi-toge), and even bizarre and creepy humor (“Hey, you’re good!”). I have no evidence that any early Japanese game writer was thinking of folktales when writing their NPC dialogue, but I think there’s an argument to be made that this style of storytelling can be a great reference point for understanding or writing games.

Here’s another Legends of Tono story:

…One night a laborer strayed off, and, after coming back, he remained in a dazed state for some time. After this incident, four or five other workers kept going off to somewhere. Later, they said that a woman came and led them off somewhere. It is said that after returning, they couldn’t remember anything for two or three days. — Page 45

In the above story, we get a glimpse into some sort of social gender dynamic, but with a mysterious twist at the end. In these stories, each detail leads to further questions. Did people travel to this swamp? Who could have yelled out “Hey, you’re good!” What was the woman doing? Is she real? Why would this story have been passed down? It’s left up to the reader.

The end of the grueling PS2 JRPG Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne comes to mind, where you’re asked to take sides. I likened this to picking a political party to root for — arguably a misinterpretation on my part. But it’s the power of stories to allow for misinterpretation. Besides, to me, it’s how we intuitively respond to and act upon a story that matters more — rather than precisely understanding its plot or emotional beats.

Miscellany has the power of “potential for misinterpretation.” That’s what can make it fun to write: imagining where a player encounters the text, and how it can pull interpretations in multiple directions. Writing miscellany feels like taking a slice of real life, in-person interaction, and trying to abstract it into some corner of a digital world. It’s also why I really appreciate the strange, off-beat details and text that so many games are lovingly scattered with. It’s easy to think of it all as ‘flavor text,’ but I’d also like this kind of text (and the game moments they accompany) to be considered as something vital to allowing games to reflect our real lives back at us.

Potential for misinterpretation is a neat idea. I feel like death stranding does the opposite. Many of the lore documents plainly spell out an aspect of the world. They don't feel like pieces of writing to be enjoyed by the player. They feel like bits intended for lore youtubers to incorporate in their theories. Other AAA games like Doom Eternal give similar vibes with their lore docs.

I loved this post man. I feel like my background as a fiction writer has influenced me to take a more formal lens to dialogue in prose, and I’ve often felt a little dissatisfied with the pressure to have literary elements add up to really neat packages of what plot, characterization, and narrative look like. So this study on miscellany was really refreshing and eye-opening!